Introduction

As OSK gets ready for space based operations with the imminent launch of its first two satellites, GHOSt 1 & 2, the analytics team has been operationalizing how it detects methane from space. A recent study estimated that pipelines emit 2.7 metric tons of methane per km per year, equivalent to 10M metric tons of methane annually. The GHOSt constellation enables persistent monitoring while maintaining high sensitivity to Methane. OSK’s goal is to provide a tool to the midstream industry that enables them to quickly identify and fix methane leaks.

Technology

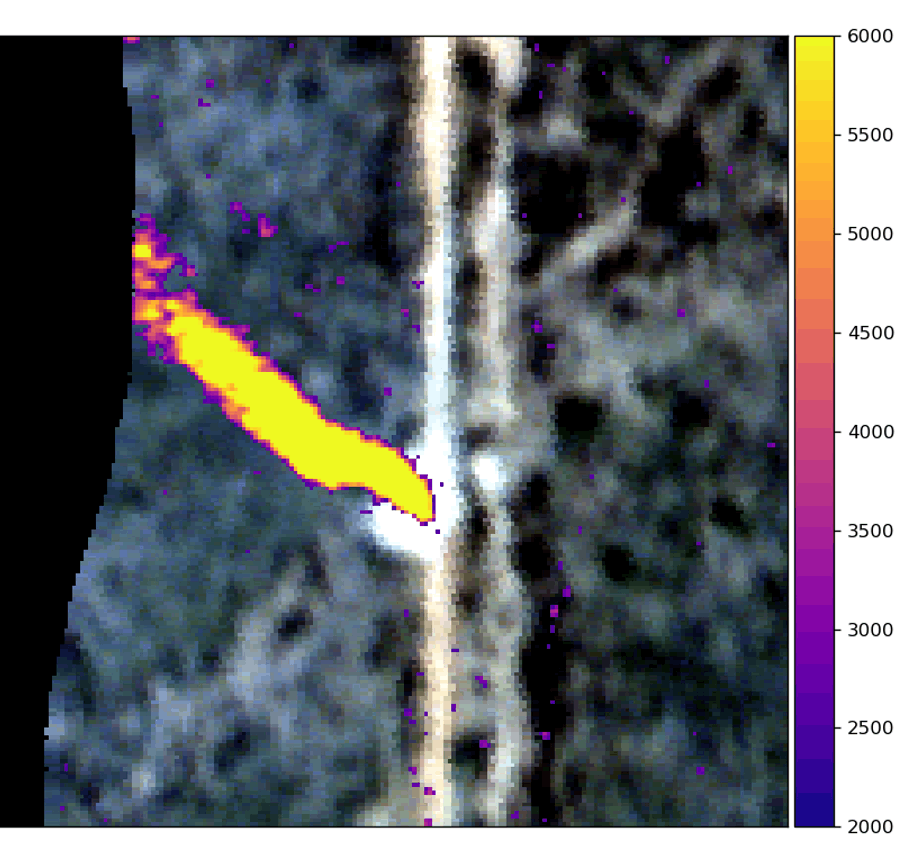

Currently, gas detection in hyperspectral imagery relies on two main algorithms, the matched filter and iterative maximum a posteriori differential optical absorption spectrometry (IMAP-DOAS) [Methane Detection Methods]. Typically, the matched filter is implemented in a manner such that an estimate of the gas concentration pathlength is provided. The detection maps, as shown in Figure 1, are then further processed to estimate the integrated mass enhancement (IME) of the methane plume and converted to a leak rate estimate [IME Method]. At OSK, we are constantly trying to push the envelope and improve upon our baseline detection and estimation algorithms. Incorporating AI into our processing chain allows OSK to offer superior, automated detection capabilities, enabling our customers to quickly respond and fix leaks.

Figure 1. Example methane plume concentration pathlength (ppm-m) detection and estimate.

To date, OSK has monitored over 35,000 km of oil and gas pipelines. That amount of data can quickly become overwhelming for an analyst to parse. To overcome this scalability issue, OSK has developed an AI algorithm to replace the human-in-the-loop and automatically declare plume detections within an image, enabling reliable near real-time warning for our customers.

Datasets and Methods

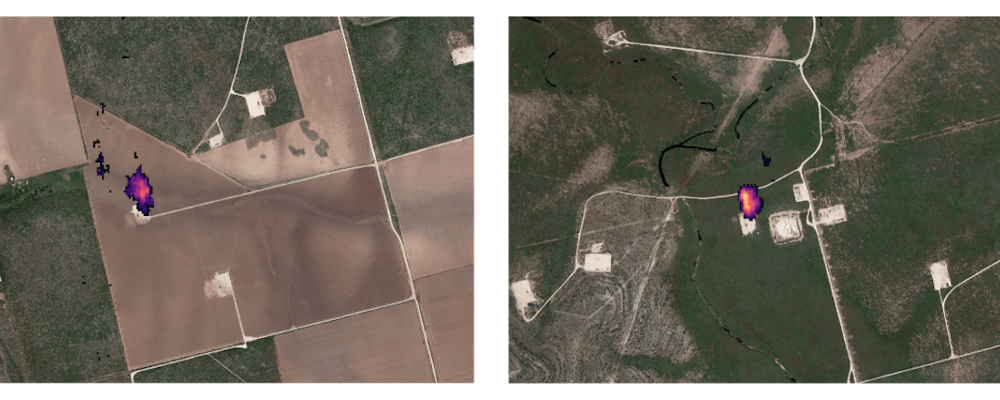

To demonstrate OSKs technology, we have executed the OSK processing chain on data collected from one of our airborne campaigns using the “Kato” sensor, which typically has a resolution of around 0.5 meters. Additionally, we have remapped the airborne data to approximate the upcoming Ghost sensor specifications, by convolving with an approximate point spread function (PSF), resampling, and adjusting the SNR. In doing so, we demonstrate what a methane detection might look like in our satellite imagery, Figure 2. Additionally, processing the remapped data allows us to validate our processing and quickly deploy algorithms to the Ghost sensors. Actual detections from the Ghost 2 sensor using these same algorithms are shown in Figure 3 for comparison.

Figure 2. Example detection from space after remapping the data in Figure 1. Edges are tapered in magnitude due to the convolution kernel in the simulation.

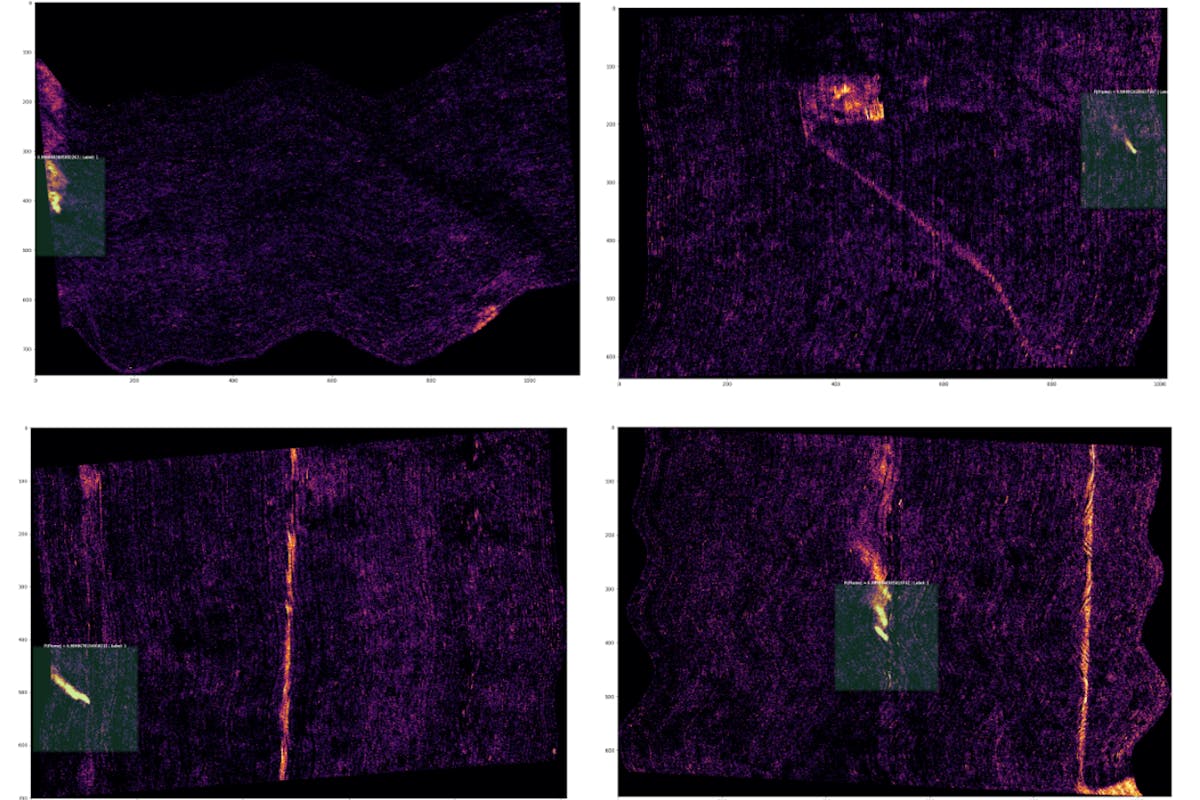

After estimating the plume concentration pathlength, the automated detection pipeline was run over the images. Each image contained plumes and common confusers. The model output included detection boxes with confidence scores, which allowed for automated alerts to be passed to the customer. Along with the detection positions an estimate of the leak rate may be computed from the integrated mass enhancement (IME), which takes into account the pixel size, plume length, and local wind speed.

Results

Comparing the airborne, Figure 1, versus the simulated spaceborne, Figure 2, detection map, we note a difference in magnitude of the concentration pathlength between the two images. This is due to the larger GSD in the space based sensor which reduces the average concentration of gas in that cell. However, this should not impact the results of the IME estimation much, as the GSD is accounted for in the calculation.

Figure 3. Detections from OSK’s Ghost 2 Sensor indicating possible leaks on well pads.

Two examples of detections from the Ghost 2 sensor are shown in Figure 3. Both demonstrate good agreement in overall shape and magnitude with the remapped detection in Figure 2, validating our simulation, and enabling OSK to minimize the transition of algorithms developed on aerial data to satellite data.

Figure 4. Example automated plume detection results from the AI model.

Example detection results from the AI model are shown in Figure 4. Plumes of various sizes are automatically detected with high confidence, as indicated by the transparent boxes. Just as important is the fact that the bright dirt roads and other confusers are successfully identified as negatives. Thus, the client is not burdened by over reporting many false alarms and can focus their attention on the true plumes.

Hyperspectral technology and AI enable automated detection of methane plumes from space to combat climate change.

For more information, or if you want to discuss our work, please reach out to us at info@orbitalsidekick.com

References

1 Murphy, E., & Yu, J. (2022, October 4). Research shows gathering pipelines in the Permian Basin leaking 14 times more methane than officials estimate. Environmental Defense Fund. https://blogs.edf.org/energyexchange/2022/10/04/research-shows-gathering-pipelines-in-the-permian-basin-leaking-14-times-more-methane-than-officials-estimate/

2 Thorpe, A. K., Frankenberg, C., Thompson, D. R., Duren, R. M., Aubrey, A. D., Bue, B. D., Green, R. O., Gerilowski, K., Krings, T., Borchardt, J., Kort, E. A., Sweeney, C., Conley, S., Roberts, D. A., & Dennison, P. E. (2017). Airborne doas retrievals of methane, carbon dioxide, and water vapor concentrations at high spatial resolution: Application to aviris-ng. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 10(10), 3833–3850. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-3833-2017

3 Varon, D. J., Jacob, D. J., McKeever, J., Jervis, D., Durak, B. O., Xia, Y., & Huang, Y. (2018). Quantifying methane point sources from fine-scale satellite observations of atmospheric methane plumes. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 11(10), 5673–5686. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-5673-2018

Kevin Brodie is the Director of Machine Learning at Orbital Sidekick. He holds degrees in Kinesiology, Mechanical Engineering, and Electrical Engineering from the University of Maryland, UMBC, and Johns Hopkins University. Prior to joining Orbital Sidekick, Kevin developed algorithms for radar systems. In his free time he enjoys vacationing with his family, following Terps sports, and playing guitar.